Interesting fact…African American women only account for three percent of the STEM profession. In the mid 80s when Kimberly Bryant was an undergraduate electrical engineer major at Vanderbilt University, the statistics shows that women engineers were on the rise.

“Statistics say, that I started Vanderbilt at a time women in engineering was at its peek,” Bryant recalled. “When I graduated, women accounted for 36 percent of the degrees in computer science. Since that time that number has plummeted. Depending on the study you look at, it’s between one and eight percent. For women of color it’s even less. African American women only receive about three percent of the degrees and Latinos and Native Americans account for less than one percent. This startles me.”

As more opportunities are available for women, it’s surprising that STEM fields are seeing a decrease. Perhaps it’s because young girls aren’t being prepared for that type of industry.

Circa the late 1960’s and 70’s, Byrant grew up in a time when she was really interested in chemistry sets and everything that her older brother was getting for Christmas. “But everything I got were Barbie Dolls and all of the girlie things, including that dress I have on in this picture,” Bryant said while sharing a picture of her younger self. “I was very adaptavant that this is what was expected of a girl growing up in the 60’s in the inner city neighborhoods of Memphis, Tennessee. I had never seen an engineer anywhere. I didn’t even know what an engineer was other than Thomas the Tank.”

Fast forward some years later to the birth of Bryant’s daughter Kai and like her mother had done, Bryant dressed her daughter in the ruffled dresses with ribbons and pigtails and gave her all of the toys that girls are “suppose” to like.

“I just knew she was going to be the next Misty Copeland before the world had ever heard of Misty Copeland,” she says jokingly. “But Kai had different thoughts. The things that Kai was very much interested in were things like Gameboys, Nintendo, dungeons and dragons. She was very much what we like to call a tech native. She spent most of her time working with her hands and with robotics. None of the girly girl stuff for Kai.”

When Kai was 10 years old she attended to a summer camp at Stanford University to learn how to build the videogames that she loved to play.

“When I return pick her up, she runs out with excitement and tells me about all of the things that she learned to create. My heart was full. She had connected with this passion and found something that really made her excited about the future.”

As they continued to talk about what she had learned, Kai shared something with her mother that changed her entire outlook on engineering. She said “Mommie, I loved being in camp and the games and things that I built, but sometimes they didn’t pay as much attention to me. I raised my hand a lot, but they kept looking over me.”

In a classroom of about 40-45 kids, there were only three girls and Kai was the only student of color.

“Kai’s introduction to engineering was very much like mine,” referring to her time at Vanderbilt. “There was nothing on the college campus that was reminiscent of my life growing up in Memphis. It was very hard for me coming into that atmosphere. There was no-one who looked like me or came from my socio-economic background. I felt so very isolated. Those four years of college were the hardest years of my life. In that moment I was afraid that the light and passion I saw as she was running down the stairs from the camp would be lost. And as a parent I was afraid.”

Kimberly Bryant is the founder of Black Girls CODE, a non-profit dedicated to encouraging girls of color to pursue careers in the STEM industries.

Initially she didn’t know what she was going to do, but she knew she had to do something. The concerned mother didn’t just wanted to create an easier pathway for her daughter, but for all girls that looked like her. A place that was a lot more kinder than what she had experienced at Vanderbilt. That was the beginning of Black Girls CODE.

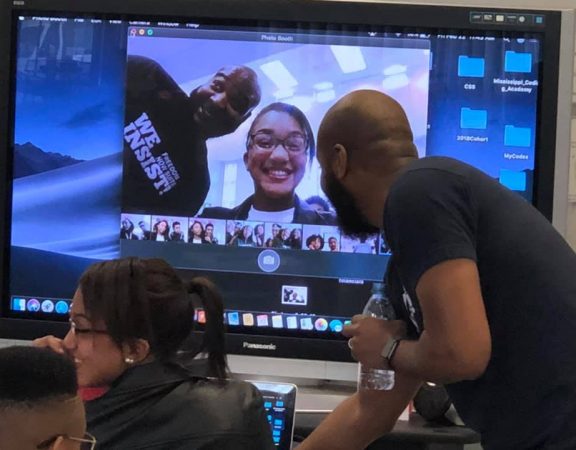

Black Girls CODE is devoted to showing the world that black girls can code. The non-profit introduces computer coding lessons to young girls from underrepresented communities. The ultimate goal is to provide African-American youth with the skills to occupy some of the 1.4 million computing job openings expected to be available in the U.S. by 2020, and to train 1 million girls by 2040.

The organization is open girls ages 12-17 and hosts after school programs, competitions in which the girls design mobile apps that help solve problems in their communities and they are mentored by coding professionals from Google, Facebook and other tech companies. To date Black Girls CODE has helped more than 9,000 tech divas and is now an international organization with chapters in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“The work that we’ve done with BCG is so much more than teaching them how to code,” Bryant believes. “It’s about teaching them self confidence, resiliency, efficacy and how to be effective global citizens in the world. When I think about all of the work that Black Girls CODE has done, I remain encouraged daily by their resilience and their bravery and what they are able to achieve and how they’ve excelled.”

For more information about Black Girls CODE, click here.